A couple in rural Alabama lost everything—home, belongings, business—after $50 worth of cannabis and a single legal pharmaceutical pill were found in a drug taskforce raid. The case raises questions about asset forfeiture laws, and their invitation to abuse by overzealous cops.

A couple in rural Alabama lost everything—home, belongings, business—after $50 worth of cannabis and a single legal pharmaceutical pill were found in a drug taskforce raid. The case raises questions about asset forfeiture laws, and their invitation to abuse by overzealous cops.

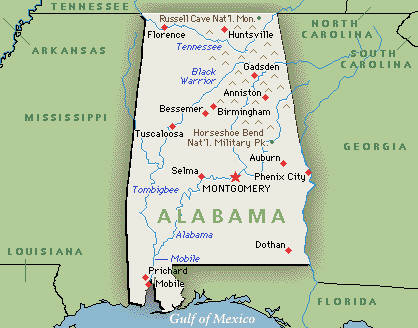

Bob and Teresa Almond lived in their home in the Alabama town of Woodland for 27 years, raising children and running a business there. Their modest dream of comfortable retirement in the house, with money from chickens they raised on the property, came crashing down on Jan. 31, 2018, when the Randolph County Drug Task Force raided the home—supposedly on the basis of smelling cannabis.

Lives upended

A poignant profile of their case appears on the website of a Montgomery-based social advocacy organization, the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice. As Appleseed researcher Leah Nelson relates, Teresa Almond, a 49-year-old grandmother, is still traumatized. She now spends at least part of her days sitting under the shelter of a relative's garage, clutching a firearm in fear that the deputies will come back.

The raid came after a sheriff's deputy said he detected the smell of cannabis coming from the house. On no notice, the taskforce broke down the door, detonated a flashbang grenade, ordered the Almonds to the floor at gunpoint—and ransacked the house. In addition to the estimated $50 worth of cannabis, the taskforce found a single pill of Lunesta, a prescription sleep aid. This was deemed illegal because the pill was not inside the bottle that was printed with Greg's name, clearly indicating it was his prescription.

Deputies handcuffed the Almonds, and booked them into the Randolph County jail. They were charged with second-degree marijuana possession, a misdemeanor, and felony possession of a controlled substance—because the Lunesta pill was not in its original packaging. Neither of them ever arrested before, the couple spent the night in jail.

Meanwhile, Greg’s family watched from their home across the road as deputies spent the night hauling out tens of thousands of dollars worth of property—Greg's gun collection, a chainsaw, antique guitars, a coin collection, Teresa's wedding rings, and about $8,000 in cash the couple kept in safes in the back of the house. The doors were left unsecured, and the Almonds' dog was lost.

Ultimately, the felony charge was rejected by a grand jury. The misdemeanor cannabis charge is still pending. The Almonds say their adult son, who was living in the house at the time, told officers that he owned the cannabis and his parents didn't know it was there. The couple have filed a case against county authorities, asserting that their civil rights were violated, and that authorities failed to demonstrate how the seized property had any connection to criminal activity.

The case has sparked outrage locally, even if it has failed to win much national attention. Alabama Political Reporter editorializes: "Civil asset forfeiture destroyed the Almonds. Specifically, Alabama’s ridiculously broad and downright unconstitutional civil asset forfeiture laws, which allow Alabama cops to seize property even though citizens are never convicted of a crime and then forces people to prove their innocence."

The forfeiture machine

As the Appleseed Center states, civil asset forfeiture can mean big bucks for local police forces. Alabama does not track or made public its income from forfeitures—although prosecutors have pledged to create a public database in response to activist pressure.

Last year, the Appleseed Center joined with the Southern Poverty Law Center to review some 70% of civil asset forfeiture cases filed by the state in 2015. The resulting report revealed that Alabama netted nearly $2.2 million in 827 cases that year. Also that year, courts awarded law enforcement agencies 406 seized weapons, 119 vehicles, 95 electronic items and 274 other miscellaneous items, including power tools, houses and mobile homes..

In 18% of the reviewed 2015 cases in which criminal charges were filed, the charge was simple possession of cannabis and/or paraphernalia. As the Appleseed Center points out, these are "crimes that by definition do not enrich the people who commit them."

The Appleseed report details how the episode has devastated the Almonds. They had recently mortgaged their property to upgrade their chicken coops. With bitter irony, they were scheduled to sign paperwork restructuring their loans on Feb. 1, 2018. They missed that appointment because they were in jail. The house was repossessed by the bank. The couple is now living in a storage shed on the property—with a propane heater for warmth, and just a trickle of electricity from a solar panel they've installed.

"I'm not right," Teresa Almond admitted to reporter Nelson. "I have not been right since the day it happened,” she said. “That was my home. I raised all my babies in there. And my grandbabies. If my grandbabies would have been there that day, they would have hurt my grandbabies. I have nowhere to bring my babies to spend time with them. 'Cause this is not a atmosphere that I want my grandbabies in, and them remembering that we lived in a shack because of cops."

Federal forfeiture and the STATES Act

While it would have no impact on local police forces in places like Alabama, a bill pending on Capitol Hill does acknowledge that forfeiture abuse is a concern, and would impose limits on the practice by federal authorities. The Strengthening the Tenth Amendment Through Entrusting States Act (STATES Act), which was recently reintroduced, would bar federal forfeiture of any assets derived from state-legal cannabis enterprises. It would also exempt state-legal cannabis businesses from the definition of "specified proceeds of illegal activity" under the federal money laundering statutes.

As National Law Review notes, the STATES Act would make clear that federal asset forfeiture and money laundering laws are inapplicable to funds derived from state-legal cannabis activities. But, apart from drawing some attention to the issue of forfeiture abuse, this would mean little for states like Alabama—which has some of the harshest cannabis laws in the country, and not even a medical marijuana program.

Oooh, that smell

Another question raised by the egregious Almond case is whether the mere of smell of cannabis can justify search and seizure. In a win both for cannabis freedom and racial justice, Vermont's top court this January ruled in favor of a motorist whose car was searched and seized on the ostensible basis that a state trooper smelled pot—and the probable basis that he was African American. Gregory Zullo prevailed in state Supreme Court, which found that the "faint" smell of cannabis was not enough to justify seizure of his vehicle. The case was sent back to the lower court in Rutland, where the ACLU can now argue that the police acted in "bad faith," and that the stop was racially motivated.

Unfortunately, just weeks earlier the Kansas high court ruled for the police in a similar case. A divided Kansas Supreme Court upheld a cannabis conviction in a case that similarly relied on supposed olfactory evidence to justify a search. Worse, this case extended to a private home the accepted police practice in Kansas that a whiff of pot can justify the search of a vehicle. Douglas County resident Lawrence Hubbard's cannabis conviction will stand.

Cross-post to Cannabis Now

Image from Greenwhich Mean Time

Recent comments

3 weeks 3 days ago

3 weeks 3 days ago

6 weeks 4 days ago

7 weeks 3 days ago

11 weeks 3 days ago

15 weeks 2 days ago

19 weeks 2 days ago

20 weeks 18 hours ago

30 weeks 18 hours ago

34 weeks 1 day ago